The rookie wins the tournament!

The rookie wins the tournament!

By Bruce Callis

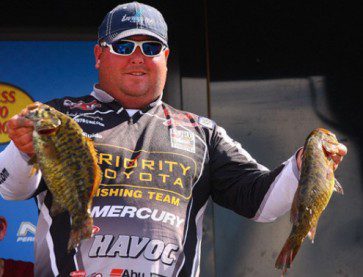

The rookie wins the tournament! The Virginia rookie on the Elite tour this year won his first tournament and a berth in the 2015 Bassmaster Classic. Yes, you read that right. Jacob Powroznik won the 2014 Evan Williams Bourbon Bassmaster Elite at Toledo Bend with a 5 fish bag of 19.11 pounds on the final day. A sweet comeback for the man that led after day 2, had a 5 fish limit for 11.13 pounds on day 3 and trailed entering the final day by almost 3 pounds.

What a finish to the final day too. With 10 minutes to go he was in a world of hurting, but culling out a 1.5 pound bass with a 5 pounder will always help. He edged out Dean Rojas, Chad Morgenthaler, Randall Tharp, and Mark Davis to win by two and a half pounds. He had no secret spot, no special bait that no one else had, he was doing the same thing everyone else was doing. A shad spawn in the morning was the big bass getter and bedding bass once the bite declined.

So why didn’t everyone else find the big bass? Toledo Bend is known for its big bass and big bag limits. Yet, so many Elite anglers finished their Day 2 with an average bass of 2 pounds. Two pounds from guys who are the cream of the bass fishing world? You are telling me that the best anglers couldn’t do better than a humble, broken down old angler like myself? I mean, didn’t they have practice days on the lake? Don’t they have the state of the art electronics to see the bass? Don’t they have the Hydrowave to excite the bass into a feeding frenzy? I mean, they have all the tools that we wish we had, on a boat we wish we were fishing out of, and yet, some don’t finish day 2 with even 10 fish. Am I missing something?

I’m pretty sure most of us are thinking the same thing; I can do better than that. I know I could have found the big girls on Toledo Bend and at least finished better than half the field. I mean, 10 bass of 3 pounds each would have put me in a tie for 44th place. I would have earned a check for $10,000 with that result. And if I had just found 1 or 2 of the big girls, who knows where I would have finished. I’m sure you are thinking the same thing; I could do that with ease.

Yeah, I know, I’m sitting myself up for a terrible day of fishing Saturday. But bass fishing can be humbling. I’ve had those days and will again, but I am not a Bassmaster Elite angler either. Where do you think you would have finished on day 2 on Toledo Bend? Or am I just missing it all?